File I/O and Exception Handling in Python

In actual development, we often encounter scenarios where data needs to be persisted. Persistence refers to transferring data from storage media that cannot store data for long periods (usually memory) to storage media that can store data for long periods (usually hard disk). The most direct and simple way to implement data persistence is to save data to files through the file system.

A computer’s file system is a method of storing and organizing computer data that makes accessing and finding data easy. The file system uses the abstract logical concepts of files and tree directories to replace the data block concepts of physical devices such as hard disks, optical disks, and flash memory. When users use the file system to save data, they don’t need to worry about which data block on the hard disk the data is actually saved to; they only need to remember the file’s path and filename. Before writing new data, users don’t need to worry about which data blocks on the hard disk are unused. The storage space management (allocation and release) on the hard disk is automatically completed by the file system, and users only need to remember which file the data was written to.

Opening and Closing Files

With a file system, we can conveniently read and write data through files. Implementing file operations in Python is very simple. We can use Python’s built-in open function to open files. When using the open function, we can specify the filename, operation mode, and character encoding through the function’s parameters, and then we can perform read and write operations on the file. The operation mode here refers to what kind of file to open (character file or binary file) and what kind of operation to perform (read, write, or append), as shown in the table below.

| Operation Mode | Specific Meaning |

|---|---|

'r' | Read (default) |

'w' | Write (truncates previous content first) |

'x' | Write, raises exception if file already exists |

'a' | Append, writes content to the end of existing file |

'b' | Binary mode |

't' | Text mode (default) |

'+' | Update (both read and write) |

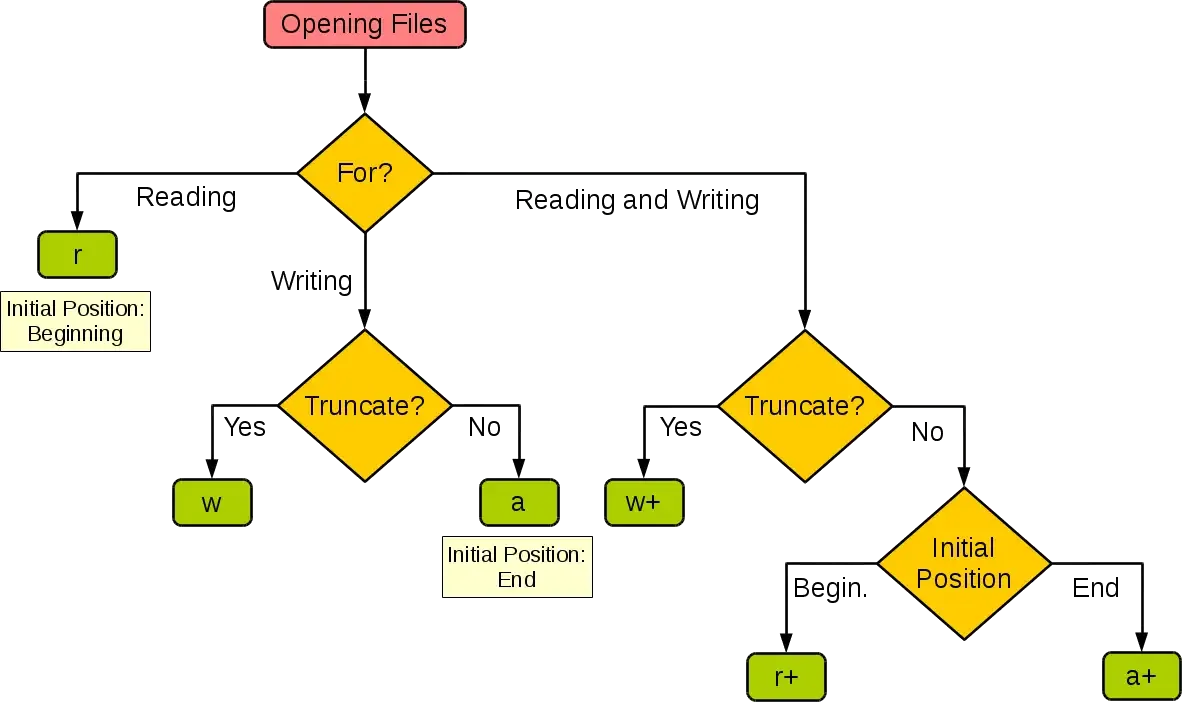

The diagram below shows how to set the operation mode of the open function according to the program’s needs.

When using the open function, if the file being opened is a character file (text file), you can specify the character encoding used for reading and writing the file through the encoding parameter. If you’re not familiar with concepts like character encoding and character sets, you can read the article “Character Sets and Character Encoding”, which won’t be elaborated on here.

After successfully opening a file using the open function, it returns a file object through which we can read and write to the file. If opening the file fails, the open function will raise an exception, which will be explained later. To close an opened file, you can use the file object’s close method, which releases the file when file operations are complete.

Reading and Writing Text Files

When opening text files with the open function, you need to specify the filename and set the file’s operation mode to 'r'. If not specified, the default value is also 'r'. If you need to specify character encoding, you can pass in the encoding parameter. If not specified, the default value is None, which means the operating system’s default encoding is used when reading the file. It’s important to note that if you cannot guarantee that the encoding method used when saving the file is consistent with the encoding method specified by the encoding parameter, it may fail to read the file due to inability to decode characters.

The following example demonstrates how to read a plain text file (generally refers to files composed only of native character encoding; compared to rich text, plain text does not contain character style control elements and can be directly read by the simplest text editor).

file = open('To the Oak Tree.txt', 'r', encoding='utf-8')

print(file.read())

file.close()Note: “To the Oak Tree” is a love poem created by teacher Shu Ting in March 1977, and it’s also one of my favorite modern poems.

In addition to using the file object’s read method to read files, you can also use a for-in loop to read line by line or use the readlines method to read the file into a list container by lines, as shown in the code below.

file = open('To the Oak Tree.txt', 'r', encoding='utf-8')

for line in file:

print(line, end='')

file.close()

file = open('To the Oak Tree.txt', 'r', encoding='utf-8')

lines = file.readlines()

for line in lines:

print(line, end='')

file.close()If you want to write content to a file, you can use w or a as the operation mode when opening the file. The former will truncate the previous text content and write new content, while the latter appends new content to the end of the original content.

file = open('To the Oak Tree.txt', 'a', encoding='utf-8')

file.write('\nTitle: "To the Oak Tree"')

file.write('\nAuthor: Shu Ting')

file.write('\nDate: March 1977')

file.close()Exception Handling Mechanism

Please note in the above code that if the file specified by the open function does not exist or cannot be opened, it will raise an exception that causes the program to crash. To make the code robust and fault-tolerant, we can use Python’s exception mechanism to appropriately handle code that may encounter situations at runtime. There are five keywords related to exceptions in Python: try, except, else, finally, and raise. Let’s look at the code below first, and then I’ll explain how to use these keywords.

file = None

try:

file = open('To the Oak Tree.txt', 'r', encoding='utf-8')

print(file.read())

except FileNotFoundError:

print('Unable to open the specified file!')

except LookupError:

print('Unknown encoding specified!')

except UnicodeDecodeError:

print('Decoding error when reading file!')

finally:

if file:

file.close()In Python, we can place code that may encounter situations at runtime in a try block, and follow the try with one or more except blocks to catch exceptions and handle them accordingly. For example, in the above code, if the file is not found, it will raise FileNotFoundError; if an unknown encoding is specified, it will raise LookupError; and if the file cannot be decoded according to the specified encoding when reading, it will raise UnicodeDecodeError. So we follow the try with three except statements to handle these three different exception situations separately. After the except statements, we can also add an else block, which is code that will execute when no exception occurs in the try block. Moreover, code in the else block will not be subject to exception catching, meaning that if an exception occurs, the program will terminate due to the exception and report exception information. Finally, we use a finally block to close the opened file and release external resources acquired by the program. Since the code in the finally block will execute whether the program is normal or abnormal, even if the exit function of the sys module is called to terminate the Python program, the code in the finally block will still be executed (because the essence of the exit function is to raise a SystemExit exception). Therefore, we call the finally block the “always execute code block”, and it’s most suitable for releasing external resources.

Python has a large number of built-in exception types. In addition to the exception types used in the above code and those encountered in previous lessons, there are many more exception types with the following inheritance structure.

BaseException

+-- SystemExit

+-- KeyboardInterrupt

+-- GeneratorExit

+-- Exception

+-- StopIteration

+-- StopAsyncIteration

+-- ArithmeticError

| +-- FloatingPointError

| +-- OverflowError

| +-- ZeroDivisionError

+-- AssertionError

+-- AttributeError

+-- BufferError

+-- EOFError

+-- ImportError

| +-- ModuleNotFoundError

+-- LookupError

| +-- IndexError

| +-- KeyError

+-- MemoryError

+-- NameError

| +-- UnboundLocalError

+-- OSError

| +-- BlockingIOError

| +-- ChildProcessError

| +-- ConnectionError

| | +-- BrokenPipeError

| | +-- ConnectionAbortedError

| | +-- ConnectionRefusedError

| | +-- ConnectionResetError

| +-- FileExistsError

| +-- FileNotFoundError

| +-- InterruptedError

| +-- IsADirectoryError

| +-- NotADirectoryError

| +-- PermissionError

| +-- ProcessLookupError

| +-- TimeoutError

+-- ReferenceError

+-- RuntimeError

| +-- NotImplementedError

| +-- RecursionError

+-- SyntaxError

| +-- IndentationError

| +-- TabError

+-- SystemError

+-- TypeError

+-- ValueError

| +-- UnicodeError

| +-- UnicodeDecodeError

| +-- UnicodeEncodeError

| +-- UnicodeTranslateError

+-- Warning

+-- DeprecationWarning

+-- PendingDeprecationWarning

+-- RuntimeWarning

+-- SyntaxWarning

+-- UserWarning

+-- FutureWarning

+-- ImportWarning

+-- UnicodeWarning

+-- BytesWarning

+-- ResourceWarningFrom the above inheritance structure, we can see that all exceptions in Python are subtypes of BaseException, which has four direct subclasses: SystemExit, KeyboardInterrupt, GeneratorExit, and Exception. Among them, SystemExit indicates that the interpreter requests to exit, KeyboardInterrupt is when the user interrupts program execution (by pressing Ctrl+c), and GeneratorExit indicates that a generator has an exception notification to exit. It’s okay if you don’t understand these exceptions; just keep learning. Worth mentioning is the Exception class, which is the parent type of regular exception types, and many exceptions inherit directly or indirectly from the Exception class. If Python’s built-in exception types cannot meet the needs of an application, we can define custom exception types, and custom exception types should also inherit directly or indirectly from the Exception class. Of course, methods can be overridden or added as needed.

In Python, you can use the raise keyword to raise exceptions (throw exception objects), and callers can catch and handle exceptions through the try...except... structure. For example, in a function, when the function’s execution conditions are not met, you can use throwing exceptions to inform the caller of the problem, and the caller can make the code recover from the exception by catching and handling the exception. The code for defining and throwing exceptions is shown below.

class InputError(ValueError):

"""Custom exception type"""

pass

def fac(num):

"""Calculate factorial"""

if num < 0:

raise InputError('Can only calculate factorial of non-negative integers')

if num in (0, 1):

return 1

return num * fac(num - 1)Call the factorial function fac, catch input error exceptions through the try...except... structure and print the exception object (display exception information). If the input is correct, calculate the factorial and end the program.

flag = True

while flag:

num = int(input('n = '))

try:

print(f'{num}! = {fac(num)}')

flag = False

except InputError as err:

print(err)Context Manager Syntax

For file objects returned by the open function, you can also use the with context manager syntax to automatically execute the file object’s close method after file operations are complete. This can make the code simpler and more elegant because you no longer need to write a finally block to execute the operation of closing the file and releasing resources. It’s important to remind everyone that not all objects can be placed in the with context syntax. Only objects that conform to the context manager protocol (have __enter__ and __exit__ magic methods) can use this syntax. Python’s standard library contextlib module also provides support for the with context syntax, which will be explained later.

The code rewritten with with context syntax is shown below.

try:

with open('To the Oak Tree.txt', 'r', encoding='utf-8') as file:

print(file.read())

except FileNotFoundError:

print('Unable to open the specified file!')

except LookupError:

print('Unknown encoding specified!')

except UnicodeDecodeError:

print('Decoding error when reading file!')Reading and Writing Binary Files

Reading and writing binary files is similar to reading and writing text files, but it’s important to note that when using the open function to open a file, if you want to perform a read operation, the operation mode is 'rb', and if you want to perform a write operation, the operation mode is 'wb'. Another point is that when reading and writing text files, the return value of the read method and the parameter of the write method are str objects (strings), while when reading and writing binary files, the return value of the read method and the parameter of the write method are bytes-like objects (byte strings). The following code implements the operation of copying an image file named guido.jpg in the current path to a file named Guido.jpg.

try:

with open('guido.jpg', 'rb') as file1:

data = file1.read()

with open('Guido.jpg', 'wb') as file2:

file2.write(data)

except FileNotFoundError:

print('The specified file cannot be opened.')

except IOError:

print('Error occurred when reading or writing file.')

print('Program execution completed.')If the image file to be copied is very large, reading the file content directly into memory at once may cause very large memory overhead. To reduce memory usage, you can pass a size parameter to the read method to specify the number of bytes to read each time, and complete the above operation through a loop of reading and writing, as shown in the code below.

try:

with open('guido.jpg', 'rb') as file1, open('Guido.jpg', 'wb') as file2:

data = file1.read(512)

while data:

file2.write(data)

data = file1.read()

except FileNotFoundError:

print('The specified file cannot be opened.')

except IOError:

print('Error occurred when reading or writing file.')

print('Program execution completed.')Summary

Through file read and write operations, we can implement data persistence. In Python, you can obtain file objects through the open function, and implement file read and write operations through the file object’s read and write methods. Programs may encounter unpredictable exceptional situations at runtime, and Python’s exception mechanism can be used to handle these situations. Python’s exception mechanism mainly includes five core keywords: try, except, else, finally, and raise. The except statement after try is not required, and the finally statement is not required either, but one of the two must be present. There can be one or more except statements, and multiple except statements will match specified exceptions in the order they are written. If an exception has been handled, it will not enter subsequent except statements. In except statements, you can also specify multiple exception types simultaneously through tuples for catching. If no exception type is specified after the except statement, it defaults to catching all exceptions. After catching an exception, you can use raise to throw it again, but it’s not recommended to catch and throw the same exception. It’s not recommended to catch all exceptions without understanding the logic, as this may mask serious problems in the program. Finally, I want to emphasize one point: do not use the exception mechanism to handle normal business logic or control program flow. Simply put, don’t abuse the exception mechanism, which is a common mistake made by beginners.