Python Functions and Modules

Before explaining the content of this lesson, let’s first study a math problem. Please tell me how many positive integer solutions the following equation has.

$$ x_{1} + x_{2} + x_{3} + x_{4} = 8 $$

You may have already thought that this problem is actually equivalent to dividing 8 apples into four groups with at least one apple in each group, and is also equivalent to placing three dividers among the 7 gaps separating 8 apples to divide the apples into four groups. So the answer is $\small{C_{7}^{3} = 35}$, where $\small{C_{7}^{3}}$ represents the number of combinations of choosing 3 from 7, and its calculation formula is as follows.

$$ C_m^n = \frac {m!} {n!(m-n)!} $$

Based on what we’ve learned before, we can calculate $\small{m!}$, $\small{n!}$, and $\small{(m-n)!}$ separately using loops to perform cumulative multiplication, and then obtain the combination number $\small{C_{m}^{n}}$ through division, as shown in the following code.

"""

Input m and n, calculate the value of combination C(m,n)

Version: 1.0

Author: Luo Hao

"""

m = int(input('m = '))

n = int(input('n = '))

# Calculate factorial of m

fm = 1

for num in range(1, m + 1):

fm *= num

# Calculate factorial of n

fn = 1

for num in range(1, n + 1):

fn *= num

# Calculate factorial of m-n

fk = 1

for num in range(1, m - n + 1):

fk *= num

# Calculate the value of C(M,N)

print(fm // fn // fk)Input:

m = 7

n = 3Output:

35I wonder if everyone has noticed that in the code above, we performed three factorial operations. Although the values of $\small{m}$, $\small{n}$, and $\small{m - n}$ are different, the three code segments are not substantially different and are duplicate code. World-class programming master Martin Fowler once said: “Code has many bad smells, and duplication is the worst!” To write high-quality code, we must first solve the problem of duplicate code. For the code above, we can encapsulate the factorial functionality into a code block called a “function”, and wherever we need to calculate factorials, we only need to “call the function” to achieve reuse of the factorial functionality.

Defining Functions

Mathematical functions usually take forms like $\small{y = f(x)}$ or $\small{z = g(x, y)}$. In $\small{y = f(x)}$, $\small{f}$ is the function name, $\small{x}$ is the independent variable of the function, and $\small{y}$ is the dependent variable of the function; while in $\small{z = g(x, y)}$, $\small{g}$ is the function name, $\small{x}$ and $\small{y}$ are the independent variables of the function, and $\small{z}$ is the dependent variable of the function. Functions in Python are consistent with this structure. Each function has its own name, independent variables, and dependent variables. We usually call the independent variables of Python functions parameters, and the dependent variables are called return values.

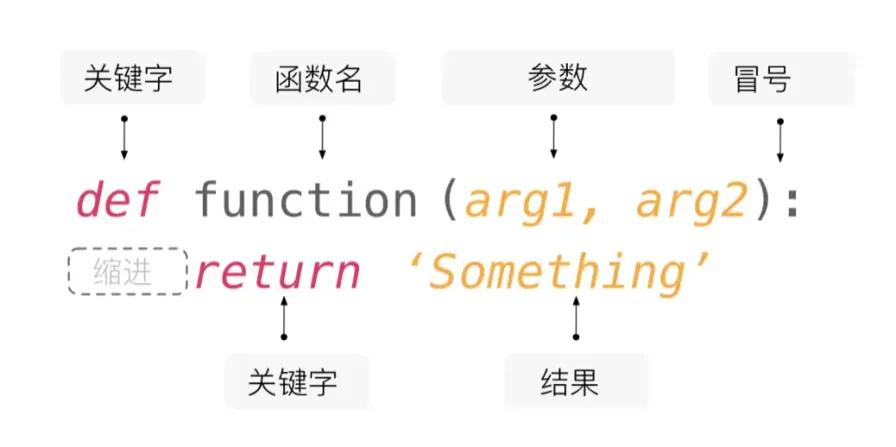

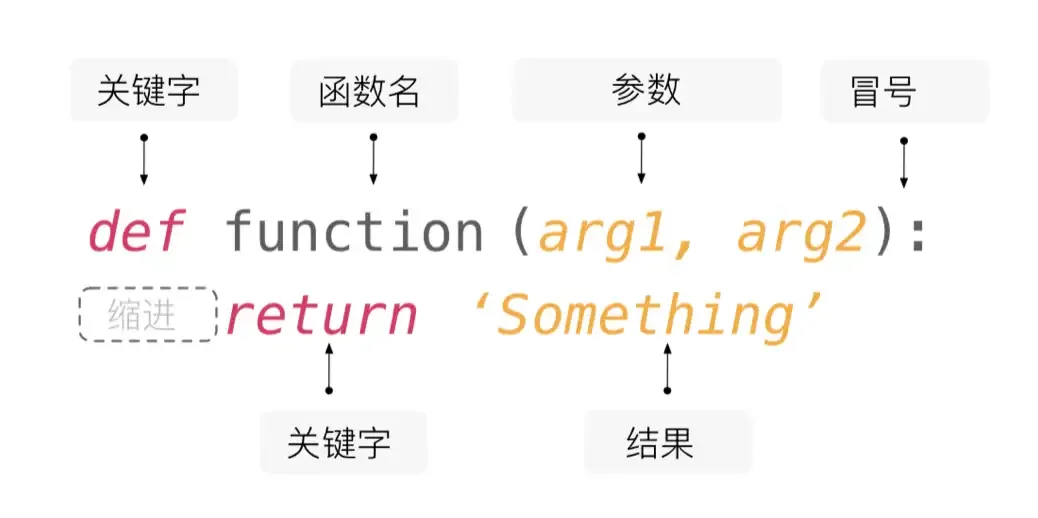

In Python, you can use the def keyword to define functions. Like variables, each function should have a nice name, and the naming rules are the same as variable naming rules (everyone should quickly recall the variable naming rules we talked about before). After the function name, you can set function parameters in parentheses, which are the independent variables we just mentioned. After the function is executed, we return the function’s execution result through the return keyword, which is the dependent variable we just mentioned. If there is no return statement in the function, the function will return None, which represents an empty value. Additionally, functions can have no independent variables (parameters), but the parentheses after the function name are required. What a function does (the code to be executed) is placed after the function definition line through code indentation, similar to the code blocks of branch and loop structures we saw before, as shown in the figure below.

Next, we’ll put the factorial operation from the previous code into a function to refactor the above code. So-called refactoring is adjusting the structure of code without affecting the code execution results. The refactored code is as follows.

"""

Input m and n, calculate the value of combination C(m,n)

Version: 1.1

Author: Luo Hao

"""

# Define factorial function using the def keyword

# The independent variable (parameter) num is a non-negative integer

# The dependent variable (return value) is the factorial of num

def fac(num):

result = 1

for n in range(2, num + 1):

result *= n

return result

m = int(input('m = '))

n = int(input('n = '))

# When calculating factorials, we don't need to write duplicate code but directly call the function

# The syntax for calling a function is to follow the function name with parentheses and pass in parameters

print(fac(m) // fac(n) // fac(m - n))You can feel that the code above is simpler and more elegant than the previous version. More importantly, the factorial function fac we defined can be reused in other code that needs to calculate factorials. So, using functions can help us encapsulate functionally independent and reusable code. When we need this code, instead of writing duplicate code again, we reuse existing code by calling functions. In fact, in Python’s standard library math module, there is already a function called factorial that implements the factorial functionality. We can directly import the math module with import math, and then use math.factorial to call the factorial function; we can also directly import the factorial function with from math import factorial to use it, as shown in the following code.

"""

Input m and n, calculate the value of combination C(m,n)

Version: 1.2

Author: Luo Hao

"""

from math import factorial

m = int(input('m = '))

n = int(input('n = '))

print(factorial(m) // factorial(n) // factorial(m - n))In the future, the functions we use will either be custom functions or functions provided in Python’s standard library or third-party libraries. If there are already available functions, we don’t need to define them ourselves. “Reinventing the wheel” is a very bad thing. For the code above, if you think the name factorial is too long and not very convenient when writing code, we can also give it an alias through the as keyword when importing the function. When calling the function, we can use the function’s alias instead of its original name, as shown in the following code.

"""

Input m and n, calculate the value of combination C(m,n)

Version: 1.3

Author: Luo Hao

"""

from math import factorial as f

m = int(input('m = '))

n = int(input('n = '))

print(f(m) // f(n) // f(m - n))Function Parameters

Positional and Keyword Arguments

Let’s write another function that determines whether three given side lengths can form a triangle. If they can form a triangle, it returns True, otherwise it returns False, as shown in the following code.

def make_judgement(a, b, c):

"""Determine if three side lengths can form a triangle"""

return a + b > c and b + c > a and a + c > bThe make_judgement function above has three parameters. These parameters are called positional parameters. When calling the function, they are usually passed in order from left to right, and the number of parameters passed must be the same as the number of parameters defined in the function, as shown below.

print(make_judgement(1, 2, 3)) # False

print(make_judgement(4, 5, 6)) # TrueIf you don’t want to give the values of the three parameters a, b, and c in order from left to right, you can also use keyword arguments, passing parameters to the function in the form of “parameter_name=parameter_value”, as shown below.

print(make_judgement(b=2, c=3, a=1)) # False

print(make_judgement(c=6, b=4, a=5)) # TrueWhen defining functions, we can use / in the parameter list to set positional-only arguments, and use * to set keyword-only arguments. Positional-only arguments means that when calling the function, parameter values can only be received according to parameter position; while keyword-only arguments can only be passed and received through “parameter_name=parameter_value”. You can look at the following examples.

# Parameters before / are positional-only arguments

def make_judgement(a, b, c, /):

"""Determine if three side lengths can form a triangle"""

return a + b > c and b + c > a and a + c > b

# The following code will produce a TypeError error with the message "positional-only arguments are not allowed to be given parameter names"

# TypeError: make_judgement() got some positional-only arguments passed as keyword arguments

# print(make_judgement(b=2, c=3, a=1))Note: Positional-only arguments are a new feature introduced in Python 3.8, so be careful when using lower versions of the Python interpreter.

# Parameters after * are keyword-only arguments

def make_judgement(*, a, b, c):

"""Determine if three side lengths can form a triangle"""

return a + b > c and b + c > a and a + c > b

# The following code will produce a TypeError error with the message "function takes 0 positional arguments but 3 were given"

# TypeError: make_judgement() takes 0 positional arguments but 3 were given

# print(make_judgement(1, 2, 3))Default Parameter Values

Python allows function parameters to have default values. We can encapsulate the dice rolling functionality from the “CRAPS gambling game” example we talked about before (Lesson 07: Applications of Branch and Loop Structures) into a function, as shown in the following code.

from random import randrange

# Define dice rolling function

# The independent variable (parameter) n represents the number of dice, with a default value of 2

# The dependent variable (return value) represents the points obtained from rolling n dice

def roll_dice(n=2):

total = 0

for _ in range(n):

total += randrange(1, 7)

return total

# If no parameter is specified, n uses the default value 2, representing rolling two dice

print(roll_dice())

# Pass in parameter 3, variable n is assigned value 3, representing rolling three dice to get points

print(roll_dice(3))Let’s look at another simpler example.

def add(a=0, b=0, c=0):

"""Add three numbers"""

return a + b + c

# Call add function without passing parameters, so a, b, c all use default value 0

print(add()) # 0

# Call add function, pass one parameter, this parameter is assigned to variable a, variables b and c use default value 0

print(add(1)) # 1

# Call add function, pass two parameters, assigned to variables a and b respectively, variable c uses default value 0

print(add(1, 2)) # 3

# Call add function, pass three parameters, assigned to a, b, c variables respectively

print(add(1, 2, 3)) # 6It should be noted that parameters with default values must be placed after parameters without default values, otherwise a SyntaxError error will occur with the error message: non-default argument follows default argument, which translates to “a parameter without a default value is placed after a parameter with a default value”.

Variable Arguments

In Python, you can use star expression syntax to make functions support variable arguments. Variable arguments means that when calling a function, you can pass 0 or any number of arguments to the function. In the future, when we develop commercial projects through team collaboration, we may need to design functions for others to use, but sometimes we don’t know how many arguments the function caller will pass to the function. This is when variable arguments come in handy.

The following code demonstrates how to use variable positional arguments to implement an add function that sums any number of numbers. When calling the function, the passed parameters will be saved to a tuple, and by traversing this tuple, we can get the parameters passed to the function.

# Use star expression to indicate that args can receive 0 or any number of arguments

# When calling the function, the n arguments passed will be assembled into an n-tuple and assigned to args

# If no arguments are passed, args will be an empty tuple

def add(*args):

total = 0

# Loop through the tuple that stores variable arguments

for val in args:

# Type check on parameters (only numeric types can be summed)

if type(val) in (int, float):

total += val

return total

# When calling the add function, you can pass 0 or any number of arguments

print(add()) # 0

print(add(1)) # 1

print(add(1, 2, 3)) # 6

print(add(1, 2, 'hello', 3.45, 6)) # 12.45If we want to pass several arguments in the form of “parameter_name=parameter_value”, and the specific number of arguments is also uncertain, we can also add variable keyword arguments to the function, assembling the passed keyword arguments into a dictionary, as shown in the following code.

# **kwargs in the parameter list can receive 0 or any number of keyword arguments

# When calling the function, the passed keyword arguments will be assembled into a dictionary (parameter names are keys in the dictionary, parameter values are values in the dictionary)

# If no keyword arguments are passed, kwargs will be an empty dictionary

def foo(*args, **kwargs):

print(args)

print(kwargs)

foo(3, 2.1, True, name='Luo Hao', age=43, gpa=4.95)Output:

(3, 2.1, True)

{'name': 'Luo Hao', 'age': 43, 'gpa': 4.95}Managing Functions with Modules

No matter what programming language you use to write code, naming variables and functions is a headache because we encounter the embarrassing situation of naming conflicts. The simplest scenario is defining two functions with the same name in the same .py file, as shown below.

def foo():

print('hello, world!')

def foo():

print('goodbye, world!')

foo() # Guess what calling the foo function will outputOf course, we can easily avoid the above situation, but if a project is developed collaboratively by a team with multiple people, there may be multiple programmers who all define functions named foo. How do we resolve naming conflicts in this situation? The answer is actually very simple. In Python, each file represents a module, and we can have functions with the same name in different modules. When using functions, we import the specified module with the import keyword and then use the fully qualified name (module_name.function_name) calling method to distinguish which module’s foo function we want to use, as shown in the following code.

module1.py

def foo():

print('hello, world!')module2.py

def foo():

print('goodbye, world!')test.py

import module1

import module2

# Use "module_name.function_name" (fully qualified name) to call functions

module1.foo() # hello, world!

module2.foo() # goodbye, world!When importing modules, you can also use the as keyword to alias the module, so we can use a shorter fully qualified name.

test.py

import module1 as m1

import module2 as m2

m1.foo() # hello, world!

m2.foo() # goodbye, world!In the two code segments above, we imported the modules that define functions. We can also use from...import... syntax to directly import the functions we need to use from modules, as shown in the following code.

test.py

from module1 import foo

foo() # hello, world!

from module2 import foo

foo() # goodbye, world!However, if we import functions with the same name from two different modules, the later imported function will replace the previous import, just like in the code below. Calling foo will output goodbye, world! because we first imported foo from module1, then imported foo from module2. If the two from...import... statements were reversed, it would be a different story.

test.py

from module1 import foo

from module2 import foo

foo() # goodbye, world!If you want to use the foo function from both modules in the code above, there is still a way. You may have already guessed it - still use the as keyword to alias the imported functions, as shown in the following code.

test.py

from module1 import foo as f1

from module2 import foo as f2

f1() # hello, world!

f2() # goodbye, world!Modules and Functions in the Standard Library

Python’s standard library provides a large number of modules and functions to simplify our development work. The random module we used before provides functions for generating random numbers and random sampling; the time module provides functions related to time operations; and the math module we used before includes a series of mathematical functions for calculating sine, cosine, exponents, logarithms, etc. As we learn Python more deeply, we will use more modules and functions.

There is also a class of functions in Python’s standard library that can be used directly without import. We call them built-in functions. These built-in functions are not only useful but also commonly used. The following table lists some of the built-in functions.

| Function | Description |

|---|---|

abs | Returns the absolute value of a number, e.g., abs(-1.3) returns 1.3. |

bin | Converts an integer to a binary string starting with '0b', e.g., bin(123) returns '0b1111011'. |

chr | Converts Unicode encoding to the corresponding character, e.g., chr(8364) returns '€'. |

hex | Converts an integer to a hexadecimal string starting with '0x', e.g., hex(123) returns '0x7b'. |

input | Reads a line from input and returns the string read. |

len | Gets the length of strings, lists, etc. |

max | Returns the maximum value among multiple arguments or an iterable object, e.g., max(12, 95, 37) returns 95. |

min | Returns the minimum value among multiple arguments or an iterable object, e.g., min(12, 95, 37) returns 12. |

oct | Converts an integer to an octal string starting with '0o', e.g., oct(123) returns '0o173'. |

open | Opens a file and returns a file object. |

ord | Converts a character to its corresponding Unicode encoding, e.g., ord('€') returns 8364. |

pow | Power operation, e.g., pow(2, 3) returns 8; pow(2, 0.5) returns 1.4142135623730951. |

print | Print output. |

range | Constructs a range sequence, e.g., range(100) produces an integer sequence from 0 to 99. |

round | Rounds a number to a specified precision, e.g., round(1.23456, 4) returns 1.2346. |

sum | Sums items in a sequence from left to right, e.g., sum(range(1, 101)) returns 5050. |

type | Returns the type of an object, e.g., type(10) returns int; while type('hello') returns str. |

Summary

Functions are encapsulations of functionally independent and reusable code. Learning to define and use functions allows us to write higher quality code. Of course, Python’s standard library already provides us with a large number of modules and common functions. Using these modules and functions well allows us to do more with less code; if these modules and functions cannot meet our requirements, we may need to define custom functions and then manage these custom functions through the concept of modules.