Python Loop Structures

When writing programs, we often encounter scenarios where we need to repeatedly execute certain instructions. For example, if we need to output “hello, world” on the screen every second for an hour, the following code can accomplish this once. To continue for an hour, we would need to write this code 3600 times. Would you be willing to do that?

import time

print('hello, world')

time.sleep(1)Note: Python’s built-in

timemodule’ssleepfunction can pause program execution. The parameter1represents the number of seconds to sleep, and can be anintorfloattype, for example0.05represents50milliseconds. We’ll cover functions and modules in later lessons.

To handle scenarios like the one above, we can use loop structures in Python programs. A loop structure is a program construct that controls the repeated execution of certain instructions. With such a structure, the code above doesn’t need to be written 3600 times, but rather written once and placed in a loop structure to repeat 3600 times. In Python, there are two ways to construct loop structures: for-in loops and while loops.

for-in Loops

If we know exactly how many times a loop should execute, we recommend using a for-in loop. For example, in the scenario mentioned above that repeats 3600 times, we can use the following code. Note that the code block controlled by the for-in loop is also constructed through indentation, just like in branch structures. We call the code block controlled by the for-in loop the loop body, and the statements in the loop body are typically executed repeatedly according to the loop’s settings.

"""

Output "hello, world" every 1 second for 1 hour

Author: Luo Hao

Version: 1.0

"""

import time

for i in range(3600):

print('hello, world')

time.sleep(1)It should be noted that range(3600) in the code above constructs a range from 0 to 3599. When we place such a range in a for-in loop, the loop variable i can sequentially take out integers from 0 to 3599, which causes the statements in the for-in code block to repeat 3600 times. Of course, the range function is very flexible. The following list shows examples of using the range function:

range(101): Can be used to generate integers from0to100, note that101is not included.range(1, 101): Can be used to generate integers from1to100, equivalent to a left-closed, right-open setting, i.e.,[1, 101).range(1, 101, 2): Can be used to generate odd numbers from1to100, where2is the step (stride), i.e., the increment value each time, and101is not included.range(100, 0, -2): Can be used to generate even numbers from100to1, where-2is the step (stride), i.e., the decrement value each time, and0is not included.

You may have noticed that the output and sleep operations in the code above don’t use the loop variable i. For for-in loop structures that don’t need to use the loop variable, according to Python programming conventions, we usually name the loop variable _. The modified code is shown below. Although the result doesn’t change, writing it this way makes you look more professional and instantly raises your level.

"""

Output "hello, world" every 1 second for 1 hour

Author: Luo Hao

Version: 1.1

"""

import time

for _ in range(3600):

print('hello, world')

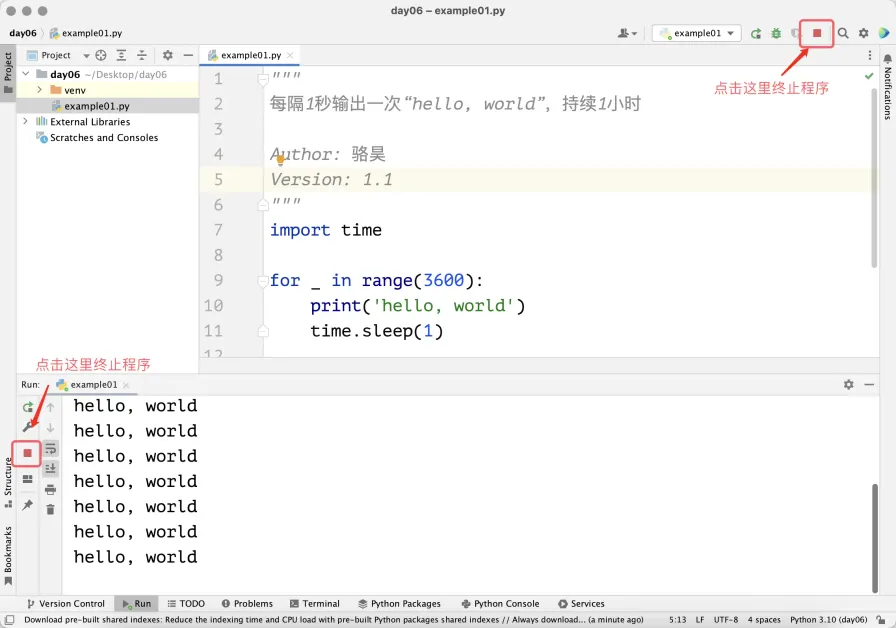

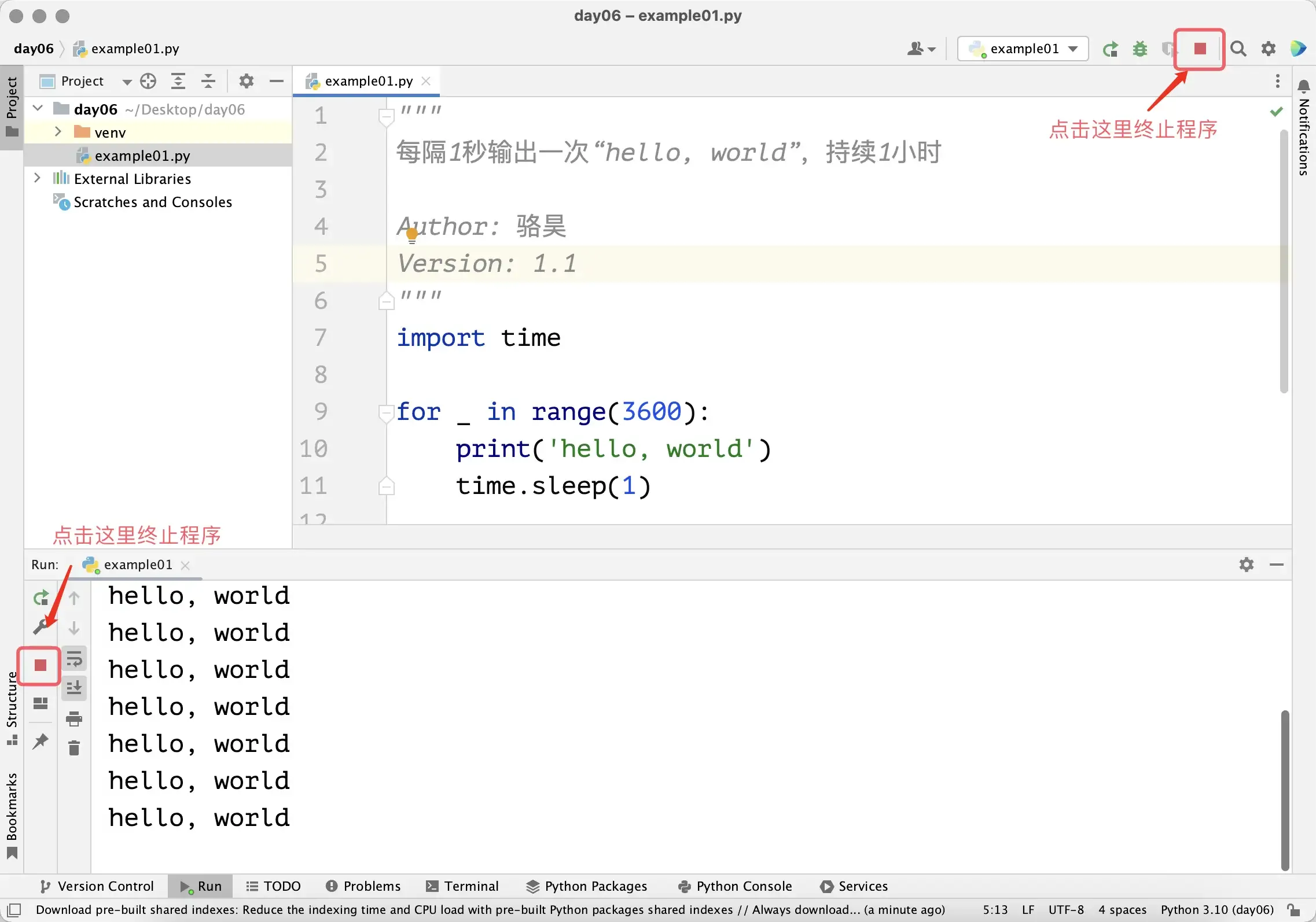

time.sleep(1)The code above takes an hour to execute. If you want to terminate the program early, in PyCharm you can click the stop button in the run window, as shown in the figure below. If running code in a command prompt or terminal, you can use the key combination ctrl+c to terminate the program.

Next, let’s use a for-in loop to implement the sum of integers from 1 to 100, i.e., $\small{\sum_{n=1}^{100}{n}}$.

"""

Sum of integers from 1 to 100

Version: 1.0

Author: Luo Hao

"""

total = 0

for i in range(1, 101):

total += i

print(total)In the code above, the variable total is used to store the cumulative result. During the loop, the loop variable i takes values from 1 to 100. For each value of i, we execute total += i, which is equivalent to total = total + i, and this statement implements the accumulation operation. So when the loop ends and we output the value of variable total, its value is the result of accumulating from 1 to 100, which is 5050. Note that the print(total) statement has no indentation and is not controlled by the for-in loop, so it won’t be executed repeatedly.

Let’s write code to sum the even numbers from 1 to 100, as shown below.

"""

Sum of even numbers from 1 to 100

Version: 1.0

Author: Luo Hao

"""

total = 0

for i in range(1, 101):

if i % 2 == 0:

total += i

print(total)Note: In the

for-inloop above, we used a branch structure to determine whether the loop variableiis an even number.

We can also modify the parameters of the range function, changing the starting value and stride to 2, to implement the sum of even numbers from 1 to 100 with simpler code.

"""

Sum of even numbers from 1 to 100

Version: 1.1

Author: Luo Hao

"""

total = 0

for i in range(2, 101, 2):

total += i

print(total)Of course, a simpler approach is to use Python’s built-in sum function for summation, which eliminates even the loop structure.

"""

Sum of even numbers from 1 to 100

Version: 1.2

Author: Luo Hao

"""

print(sum(range(2, 101, 2)))while Loops

If we need to construct a loop structure but cannot determine the number of loop repetitions, we recommend using a while loop. The while loop uses boolean values or expressions that produce boolean values to control the loop. When the boolean value or expression evaluates to True, the statements in the loop body (the code block below the while statement that maintains the same indentation) are executed repeatedly. When the expression evaluates to False, the loop ends.

Let’s use a while loop to implement the sum of integers from 1 to 100, as shown in the code below.

"""

Sum of integers from 1 to 100

Version: 1.1

Author: Luo Hao

"""

total = 0

i = 1

while i <= 100:

total += i

i += 1

print(total)Compared to the for-in loop, in the code above we added a variable i before the loop starts. We use this variable to control the loop, so after while we give the condition i <= 100. In the while loop body, besides accumulation, we also need to increment the value of variable i, so we added the statement i += 1. This way, the value of i will sequentially take 1, 2, 3, …, until 101. When i becomes 101, the while loop condition is no longer satisfied, and the code exits the while loop. At this point, we output the value of variable total, which is the result of summing from 1 to 100, which is 5050.

If we want to implement the sum of even numbers from 1 to 100, we can slightly modify the code above.

"""

Sum of even numbers from 1 to 100

Version: 1.3

Author: Luo Hao

"""

total = 0

i = 2

while i <= 100:

total += i

i += 2

print(total)break and continue

What happens if we set the while loop condition to True, making the condition always true? Let’s look at the code below, which still uses while to construct a loop structure to calculate the sum of even numbers from 1 to 100.

"""

Sum of even numbers from 1 to 100

Version: 1.4

Author: Luo Hao

"""

total = 0

i = 2

while True:

total += i

i += 2

if i > 100:

break

print(total)The code above uses while True to construct a loop with a condition that is always true, which means that without special handling, the loop won’t end. This is what we commonly call an “infinite loop”. To stop the loop when the value of i exceeds 100, we used the break keyword, which terminates the execution of the loop structure. It should be noted that break can only terminate the loop it’s in. This needs attention when using nested loop structures, which we’ll discuss later. Besides break, there’s another keyword that can be used in loop structures: continue. It can be used to abandon the remaining code in the current iteration and move directly to the next iteration, as shown in the code below.

"""

Sum of even numbers from 1 to 100

Version: 1.5

Author: Luo Hao

"""

total = 0

for i in range(1, 101):

if i % 2 != 0:

continue

total += i

print(total)Note: The code above uses the

continuekeyword to skip cases whereiis odd. Only wheniis even will execution reachtotal += i.

Nested Loop Structures

Like branch structures, loop structures can also be nested, meaning you can construct loop structures within loop structures. The following example demonstrates how to output a multiplication table (nine-nine table) through nested loops.

"""

Print multiplication table

Version: 1.0

Author: Luo Hao

"""

for i in range(1, 10):

for j in range(1, i + 1):

print(f'{i}×{j}={i * j}', end='\t')

print()In the code above, a for-in loop is used within the loop body of another for-in loop. The outer loop controls the generation of i rows of output, while the inner loop controls the output of j columns in a row. Obviously, the output of the inner for-in loop is one complete row of the multiplication table. So when the inner loop completes, we use print() to achieve a line break effect, making the subsequent output start on a new line. The final output is as follows.

1×1=1

2×1=2 2×2=4

3×1=3 3×2=6 3×3=9

4×1=4 4×2=8 4×3=12 4×4=16

5×1=5 5×2=10 5×3=15 5×4=20 5×5=25

6×1=6 6×2=12 6×3=18 6×4=24 6×5=30 6×6=36

7×1=7 7×2=14 7×3=21 7×4=28 7×5=35 7×6=42 7×7=49

8×1=8 8×2=16 8×3=24 8×4=32 8×5=40 8×6=48 8×7=56 8×8=64

9×1=9 9×2=18 9×3=27 9×4=36 9×5=45 9×6=54 9×7=63 9×8=72 9×9=81Applications of Loop Structures

Example 1: Determining Prime Numbers

Requirement: Input a positive integer greater than 1 and determine whether it’s a prime number.

Hint: A prime number is an integer greater than 1 that can only be divided by 1 and itself. For example, for a positive integer $\small{n}$, we can determine whether it’s a prime number by searching for factors of $\small{n}$ between 2 and $\small{n - 1}$. Of course, the loop doesn’t need to go from 2 to $\small{n - 1}$, because for positive integers greater than 1, factors should appear in pairs, so the loop can end at $\small{\sqrt{n}}$.

"""

Input a positive integer greater than 1 and determine if it's a prime number

Version: 1.0

Author: Luo Hao

"""

num = int(input('Please enter a positive integer: '))

end = int(num ** 0.5)

is_prime = True

for i in range(2, end + 1):

if num % i == 0:

is_prime = False

break

if is_prime:

print(f'{num} is a prime number')

else:

print(f'{num} is not a prime number')Note: In the code above, we used a boolean variable

is_prime. We first assign itTrue, assumingnumis a prime number. Next, we search for factors ofnumin the range from 2 tonum ** 0.5. If we find a factor ofnum, then it’s definitely not a prime number, so we assignis_primethe valueFalseand use thebreakkeyword to terminate the loop structure. Finally, we provide different output based on whether the value ofis_primeisTrueorFalse.

Example 2: Greatest Common Divisor

Requirement: Input two positive integers greater than 0 and find their greatest common divisor.

Hint: The greatest common divisor of two numbers is the largest number among their common factors.

"""

Input two positive integers and find their greatest common divisor

Version: 1.0

Author: Luo Hao

"""

x = int(input('x = '))

y = int(input('y = '))

for i in range(x, 0, -1):

if x % i == 0 and y % i == 0:

print(f'Greatest common divisor: {i}')

breakNote: In the code above, the

for-inloop variable values go from large to small. This way, the first factoriwe find that can divide bothxandyis the greatest common divisor ofxandy, and we usebreakto terminate the loop. Ifxandyare coprime, the loop will execute untilibecomes 1, because 1 is a factor of all positive integers, so the greatest common divisor ofxandyis 1.

The code above for finding the greatest common divisor has efficiency problems. If the value of x is 999999999998 and the value of y is 999999999999, it’s obvious that the two numbers are coprime with a greatest common divisor of 1. But using the code above, the loop would repeat 999999999998 times, which is usually unacceptable. We can use the Euclidean algorithm to find the greatest common divisor, which helps us get the desired result faster, as shown in the code below.

"""

Input two positive integers and find their greatest common divisor

Version: 1.1

Author: Luo Hao

"""

x = int(input('x = '))

y = int(input('y = '))

while y % x != 0:

x, y = y % x, x

print(f'Greatest common divisor: {x}')Note: The method and steps for solving a problem can be called an algorithm. For the same problem, we can design different algorithms, and different algorithms will differ in storage space usage and execution efficiency, and these differences represent the quality of the algorithms. You can compare the two code segments above to understand why we say the Euclidean algorithm is a better choice. In the code above, the statement

x, y = y % x, xmeans assigning the value ofy % xtoxand the original value ofxtoy.

Example 3: Number Guessing Game

Requirement: The computer generates a random number between 1 and 100. The player inputs their guess, and the computer provides corresponding hints: “higher”, “lower”, or “correct”. If the player guesses the number, the computer tells the user how many guesses it took and the game ends; otherwise, the game continues.

"""

Number guessing game

Version: 1.0

Author: Luo Hao

"""

import random

answer = random.randrange(1, 101)

counter = 0

while True:

counter += 1

num = int(input('Please enter: '))

if num < answer:

print('Higher.')

elif num > answer:

print('Lower.')

else:

print('Correct.')

break

print(f'You guessed {counter} times.')Note: The code above uses

import randomto import Python’s standard libraryrandommodule. The module’srandrangefunction helps us generate a random number in the range 1 to 100 (not including 100). The variablecounteris used to record the number of times the loop executes, i.e., how many times the user guessed. Each time the loop executes, the value ofcounterincreases by 1.

Summary

Having learned about branch structures and loop structures in Python, we can now solve many practical problems. Through this lesson, you should already know that you can use the for and while keywords to construct loop structures. If you know in advance how many times the loop structure will repeat, we usually use a for loop; if the number of repetitions of the loop structure cannot be determined, you can use a while loop. Additionally, we can use break to terminate a loop in a loop structure, and we can also use the continue keyword in a loop structure to make the loop proceed directly to the next iteration.